Review of MCA Anne Collier Exhibit

LOOKING INWARD: Developing Tray #2 (Grey), 2009. An unusual photograph with the artist herself as the subject, these floating dark room images carry on Collier’s self-analysis and introspective themes.

Appropriation is a new form of art to me that, at first glance, seems to imply potential fraud and a lack of creativity. Why photograph pre-existing objects and claim the work as your own? What new statement can you possibly make?

This technique is complex in its simplicity and generates controversy by nature; artists such as Andy Warhol have been subject to its controversial nature through copyright lawsuits. It’s kind of like “covering” in music, where one artist takes the work of another and makes it their own; it’s not intended to plagiarize–it’s intended to pay tribute and highlight new aspects of the work. Anne Collier has shed light on the powers of appropriation by its ability to culturally frame, emphasize and alter pre-existing concepts. The Museum of Contemporary Art creates the perfect setting for such recontextualizing to occur, as Collier’s photographic work is able to simultaneously provide social commentary and evoke personal thought.

As I looked eagerly to the title and caption beside each photograph, I was repeatedly frustrated at the amount of captions that briefly disclaimed that the piece was meant to be “open to interpretation.” But I subsequently realized that Collier had perhaps intended not only for the work’s subjectivity, but also for the viewer’s frustration. My reaction was a mere manipulation of her art.

From the select pieces chosen for the MCA, clear themes arose within Collier’s work. The self-help theme surfaced early on in the exhibit with different takes on depression and psychoanalysis. Eerie album covers photographed against vacant backgrounds shed a sort of “tortured artists soul” that should’ve frustrated me further in its potentially cliché nature, but instead, it intrigued me. Collier is still alive, still photographing, still sharing her emotion in her art–thus the tortured soul isn’t a cry for attention but a cry for conversation and self-awareness.

Pages from old self-help books were photographed with items of a so-called “Personality Profile Checklist.” The contradictory statements like number 61 (I am modest) and number 80 (People often admire me) served as ironic commentary on the flaws and risks of psychoanalysis. I laughed, or rather breathed a little extra air out of my nose, at the naive absoluteness of number 50 (I forgive anything) and found myself unintentionally beginning to self doubt in contemplation of number 45 (I find I am often disappointed). Perhaps the resulting self-doubt is where the irony lies.

Collier also focused on female sexuality with a commentary on the sexism that has guided photography magazines and advertisements. Photos of naked women in camera ads explicitly share this point of view, yet an ongoing series of photographs called “Woman with A Camera” comments on the female’s role in society. In the photo of Faye Dunaway holding a camera while starring as a protagonist in her own film, she is empowered, creative and admirable. Yet in other photographs, like that of Mary Elizabeth Gore’s article cover art (appropriately titled “The Woman Behind the Lens”), the woman is reduced to a prop served to idolize the camera itself. Collier displays multiple sides of the feminist role and toll, serving not to show progress but to acknowledge the blind-spot of progress itself. Her political and social commentary is often latent, but once divulged, it is never subtle.

Beyond the obvious female sexuality of Marilyn Monroe and Madonna, Collier photographed cultural icons of androgyny. A peek around the hall to a neighboring exhibit called “Body Doubles” displayed side by side pictures of Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince in identical suits, bowl cut wigs and strong makeup contouring. Their different identities are hardly distinguishable until you take a closer look.

A walk back to Collier showed her photograph of the same side-by-side shots. Prince is often considered the father of appropriation art during its “coming out” in the 1980s, so the inclusion of this artwork in Collier’s photography seems not only appropriate but brilliantly intentional. The exhibits’ cohesion highlighted the significance of the original photographs and strengthened the cultural relevance of Collier’s photographs. Amidst the dark mood of the photograph, the contrasting sexual ambiguity and provocativeness forced the contemplation of sexuality and the extent of its internal and external presence: How much of a person’s sexuality is outwardly apparent, and how much is dictated by society’s perception? Collier evidently ered on the side of societal perception.

Carrying on with the general theme of appropriation, on one of the final walls of the exhibition stood five side-by-side photographs of manilla folders with colorful words and correlating questions: Relevance, Supposition, Connection, Viewpoint, Evidence. I read that Collier had found these printed sheets abandoned on the streets of lower Manhattan, and I realized that she didn’t know what these were from any more than I did. I contemplated their significance in the same way that I imagine Collier does. They weren’t particularly interesting photographs, and standing alone none would be interesting at all. Yet for some reason, staring at all the pictures in a line, I was incredibly transfixed in the mystery of their origins and their meaning. I examined the tattered paper and imagined who had touched them before Collier found them; I reread the typed questions over and over searching for a clue to their application. I couldn’t find an answer to any of my questions, only more questions surfaced–thus the epitome of appropriation, the epitome of Collier.

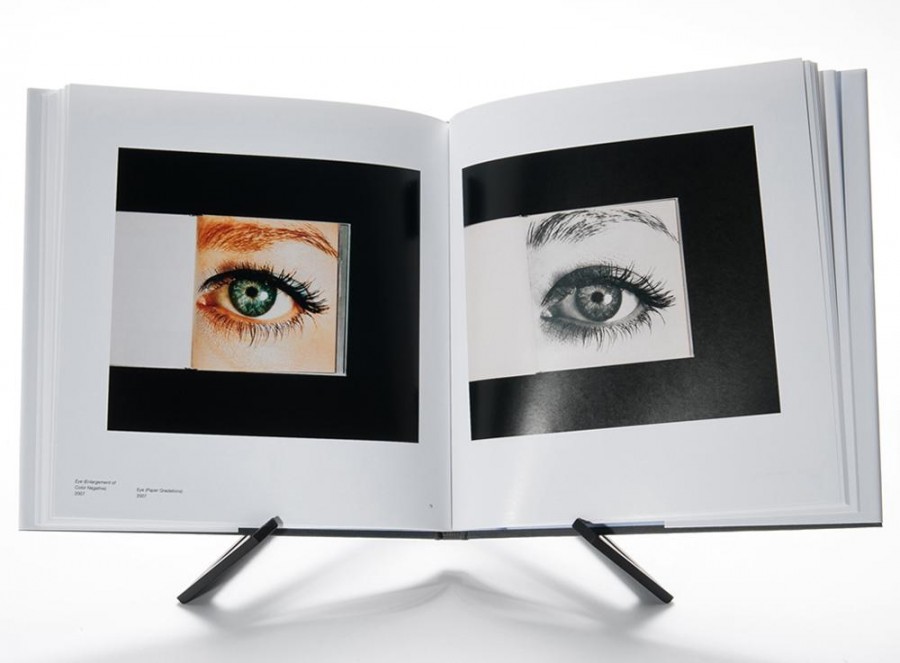

As I rounded the final corner, I found nearly three identical photographs except for slight differences in exposure. Against the vast white walls and the shiny concrete floors, Collier’s photographs of her own eyes quite literally stared at me, not asking for my opinion but looking at me as if they already knew what I was thinking.